Local Elite

https://appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/coal-strike/local-elite

New York Writers

https://appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/coal-strike/new-york-writers

National Miners Union and Other Radical Groups

https://appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/coal-strike/national-miners-union-and-other-radical-groups

This site contains films, images and text. If you are unable to view any of the content, we suggest using a different browser.

Dwight Billings, Professor of Sociology and Appalachian Studies, and Kate Black, Curator of the Appalachian Collection, discuss the historical significance of the 1931-1932 strike.

Dwight Billings, Professor of Sociology and Appalachian Studies, and Kate Black, Curator of the Appalachian Collection, discuss the elements that made the 1931-1932 strike an important event in labor history.

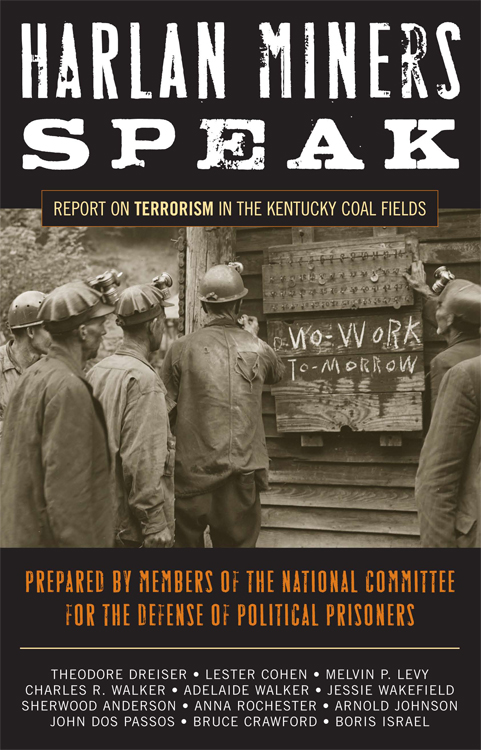

In his new introduction to the reissue of Harlan Miners Speak, an on-the-scene report from a panel of writers about the coal strike in Bell and Harlan Counties, John Hennen skillfully explains the precipitating factors of the labor unrest. The coal industry known for its boom and bust cycles was in a slump. Overproduction, lack of capital for mechanization to reduce labor costs, and competing home heating fuels all contributed to the flagging bituminous coal industry.

The Great Depression with its national reach exacerbated the already grim economy in the coalfields. Hennen writes that “[b]y late 1931, four thousand Harlan County miners, more than one in three, were out of work. Working miners made as little as eighty cents a day and worked only a few days a month.” Plagued by evictions from company houses, no other job possibilities, and even starvation, miners and their families were no longer able to rely on aid from the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Though the union had made substantial inroads into the Central Appalachian coalfields by 1930, when miners in Bell and Harlan Counties went out on strike in early May, 1931, the UMWA removed its support. Hennen attributes this abandonment to the increasingly conservative John L. Lewis, the longtime and powerful president of the UMWA, who feared that the broad-based strikes “would cut too severely into UMWA relief funds.” Lewis was influenced as well by the “American Plan.” Established by a gathering of business leaders in Chicago in 1921, the Plan outlined a “multifaceted economic system [that emphasized] free markets, individual contract, management control, nonregulation of business, and vigilance against ‘unsound’ or radical thought.“

The economic distress—both local and national—combined with the UMWA’s unwillingness to support the miners provided the opening for what Hennen calls a “radical alternative.” The National Miners Union (NMU) was the result of the American Communist Party’s decision to no longer “bore from within” established trade unions but instead to create its own unions. Pledging to back the striking miners when traditional outlets like the Red Cross were withholding aid, the NMU earned the allegiance of a small but dedicated number of miners.

The presence of a Communist Party labor union deeply disturbed the local elite of Bell and Harlan Counties. Repression of the miners and their families was swift. Coal operators, merchants, the editor of the Pineville Sun, Herndon Evans, and local police forces worked in different ways to disrupt the flow of aid to the miners and their families and depicted the strikers as anti-American. Soup kitchens were attacked, miners were beaten up in their homes, and surveillance of NMU sympathizers was intense. Herndon Evans, who was also an Associated Press correspondent, used his position to send press releases across the nation coloring the situation in the coalfields as he pleased. To counteract the “official” stories coming out of Harlan and Bell counties and to witness and document the violence directed at miners and their families, William Z. Foster, head of the American Communist Party sought the talents of writers like Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos and Sherwood Anderson. “The Dreiser Committee,” as it came to be called, traveled to Bell and Harlan counties. There the Committee observed the strike and the conditions under which the miners and their families were living. In 1932 the writers completed their report which was published by Harcourt, Brace & Company under the title Harlan Miners Speak: Report on Terrorism in the Kentucky Coal Fields.

Click on the image above and read John Hennen's introduction to the latest edition of Harlan Miners Speak (used with permission of University Press of Kentucky). When you are finished reading, begin the exercise by moving to the "Archives and the Archival Exercise" page (above right).