In just a few weeks, the University of Kentucky will welcome students, scholars and activists to campus for the 43rd annual Appalachian Studies Association (ASA) conference March 12-15. Themed "Appalachian Understories," the conference will emphasize the often obscured voices of the region, including black Appalachians.

In just a few weeks, the University of Kentucky will welcome students, scholars and activists to campus for the 43rd annual Appalachian Studies Association (ASA) conference March 12-15. Themed "Appalachian Understories," the conference will emphasize the often obscured voices of the region, including black Appalachians.

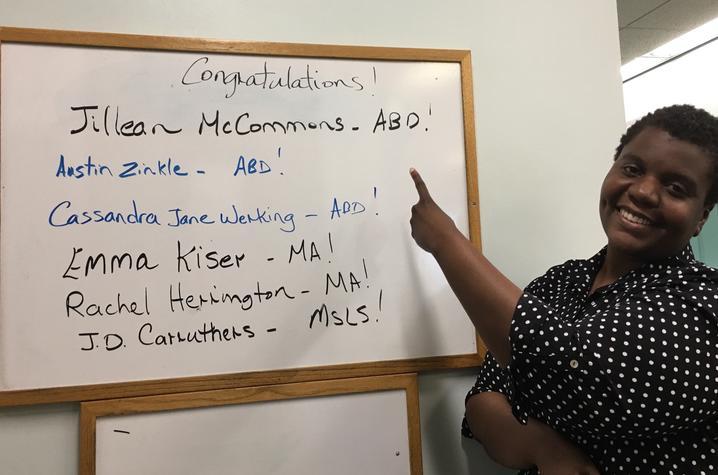

Jillean McCommons, a doctoral student in the UK College of Arts and Sciences' Department of History, studies black Appalachian history and is serving as an organizer for the upcoming conference. One of the conference's four plenaries, "Black Appalachian Women: Testimonies, Environmental Justice, and Historical Reparations," is being planned by McCommons and will feature a panel of scholars, activists and artists with ties to the region.

Originally from Detroit, Michigan, McCommons has family roots in Appalachia and says she has always been interested in black communities globally. After graduating with a bachelor's degree in English from Michigan State University, she earned two master's degrees: one in Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the second in information from the University of Michigan. She worked as a children's librarian for 10 years before coming to UK to pursue her doctoral degree.

With Black History Month happening just before the March ASA conference, UKNow sat down with McCommons to learn more about her area of research, the upcoming conference and her hopes for the future of black Appalachian studies.

UKNow: What brought you to Kentucky?

McCommons: I started playing banjo during my time as a children's librarian in Michigan, and then I started going to banjo camps in West Virginia. When I was looking for a new place to live, a friend offered me a space to stay in Richmond, Kentucky. I had been to Berea before, to their traditional music celebration, so the idea was that I'd come to Kentucky, play banjo, then figure out what to do next.

I was interested in the black community here, so I went to the libraries (naturally, being a librarian) to find books about that black experience — and I didn't find very many. I found Frank X Walker's poetry and an anthology called "Blacks in Appalachia.” Within that collection, I found an article written by a man named Jack Guillebeaux, past director of the Black Appalachian Commission, an organization founded in 1969. After reading that article, it gave me a sense of the activism black Appalachians were involved in during the '60s and '70s, so that became my area of study.

UKNow: Tell us a little more about your personal connections to Appalachia.

McCommons: Part of me being curious about Appalachia was wondering about where my grandmother and great-grandmother came from. My great-grandmother had moved from southwest Virginia to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where my grandmother was born. I started to wonder what the experience was like for black women in my family. Why did they leave the region? Why did some stay? I remember when we would ask my great-grandmother where she was from, she would just say "up in the hills." But it was something she really didn't want to talk about, and I now have some ideas as to why.

I actually went down to the place where she was from, and it was indeed "up in the hills," in Franklin County, Virginia, near Ferrum. It is a gorgeous place, but it was bittersweet knowing that my ancestors had been enslaved in that county. I think those legacies from slavery, and from Jim Crow, are why she moved around so much. When I visited, I collected some bricks and stones from the land where my ancestors were enslaved. I keep some in my car and some in my apartment to remind me where we've come from. So, I have this connection to the land that's brought me back.

UKNow: What is one of the biggest misconceptions about black communities in Appalachia?

McCommons: There's one idea that the region is all white, which is completely wrong. There are black communities, Latino communities, and indigenous communities that are completely overlooked in narratives about the region. I think people have the idea that certain things didn't go on in Appalachia, but they absolutely did. So I'm trying to add what I know, or what I found in the archives, to this grand narrative of Appalachia. Black people in Appalachia were fighting against second-class citizenship and I think it's important to highlight that.

UKNow: Tell us more about the upcoming ASA conference and its theme, "Appalachian Understories."

McCommons: "Understories" is a term from the field of ecology, which is serving as a metaphor for the conference to highlight marginalized communities. So I'm program chair of the black Appalachian theme. I think for Appalachian studies, they've always had sessions to talk about race and the region, but it was important to me that it be a main theme of the conference, also including women and LGBTQIA struggles. So, I think that for this conference, especially this year, we're trying to say, "let's really make space for marginalized voices to be heard."

UKNow: What can attendees expect to learn from the featured black panelists at the conference?

McCommons: All the panelists have a connection to the region. I'm trying to bring together scholars, activists and artists. They will include Karida Brown, a sociologist from UCLA, who will talk about her research in Harlan County, Kentucky, where her family is from. I also invited Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson from the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a longtime activist and co-executive director of the center, which has a long history of activism in the region. Another panelist is Kelly Navies from the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. She is head of their oral history program and also has roots in the region. Novelist and poet Crystal Wilkinson, who is a professor here at UK, will also participate.

My hope is for these women to come in and highlight what's happening to black communities in the region. Conversations about racial justice in the environment are often overlooked in terms of who's impacted first, whether it's by climate change, or by the choices of corporations to dump things in certain places. So environmental racism, poverty, segregation. And some people in the region are still facing the loss of black communities, people who've been pushed out by racial terror. Those things don't get covered as much as they should.

UKNow: What are your long-term hopes for the conference and Appalachian studies?

McCommons: My hope is that these themes will become a permanent part of this conference, to fully recognize that race has always played a role in the region, and that the experience of black people needs to be acknowledged. Also, indigenous people who are still here need to be acknowledged. My hope is that the ASA, people from the community and the university see that this isn't just a passing theme. This is everyday life for a lot of people.

I also would really like to see more black people attend the conference. I've made a concerted effort to call people and say, "please just come." Even if they haven't come before, or if they did come in the past and didn't feel welcome, or feel like they saw any other faces that look like theirs. I'm trying to make sure that the content is diverse, but that we also really try to get some representation of the people we see when we're traveling around Appalachia.

UK students are invited to attend the ASA conference free of charge, and the opening and closing ceremonies are free and open to the public. For more information, including a full schedule of events, visit https://appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/asa-2020.

The University of Kentucky is increasingly the first choice for students, faculty and staff to pursue their passions and their professional goals. In the last two years, Forbes has named UK among the best employers for diversity, and INSIGHT into Diversity recognized us as a Diversity Champion three years running. UK is ranked among the top 30 campuses in the nation for LGBTQ* inclusion and safety. UK has been judged a “Great College to Work for" two years in a row, and UK is among only 22 universities in the country on Forbes' list of "America's Best Employers." We are ranked among the top 10 percent of public institutions for research expenditures — a tangible symbol of our breadth and depth as a university focused on discovery that changes lives and communities. And our patients know and appreciate the fact that UK HealthCare has been named the state’s top hospital for four straight years. Accolades and honors are great. But they are more important for what they represent: the idea that creating a community of belonging and commitment to excellence is how we honor our mission to be not simply the University of Kentucky, but the University for Kentucky.